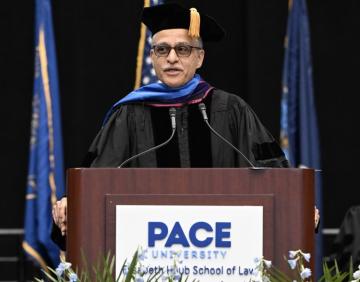

Dean Yassky Co-Authors NYT Op-Ed on Public Financing of District Attorney races

The controversy swirling around the Manhattan district attorney, Cyrus Vance Jr. for taking large campaign contributions from two defense lawyers after his office declined to prosecute their clients points to the urgent need for major reform. We need public financing of district attorney races. The good news is that New York City already has a highly regarded campaign finance system and it would be easy to include the five city district attorneys in it.

The public is entitled to both the appearance and reality of honest justice in criminal cases. But given the legality of large contributions to district attorneys and the frequency of contributions from criminal defense lawyers, the appearance of influence is inescapable. Indeed, the present system may create opportunities for actual improper influence.

Although Mr. Vance has steadfastly maintained that he acted in an entirely proper way in dismissing the cases and was not influenced by the contributions or the likelihood of receiving them, much of the public will not believe him. That kind of cynicism erodes confidence in prosecutors and ultimately can seriously impair the functioning of the criminal justice system.

When the public doesn’t trust a prosecutor, juries become skeptical of evidence and are more apt to acquit defendants who genuinely threaten public safety. More fundamentally, the criminal justice system is built on the premise of public confidence in prosecutors’ impartiality. Criminal laws are often drafted quite broadly, and we rely on a prosecutor’s judgment to screen out cases where conduct is technically in violation of the statute, but prosecution would be unfair. The appearance of undue influence by defense lawyers will undermine the legitimacy of this prosecutorial discretion.

Currently, district attorney elections are governed by New York State’s notoriously lax campaign finance laws. In Manhattan, for example, an individual may contribute up to $50,000 to a district attorney candidate — and even that generous limit has a loophole allowing additional contributions through corporations the individual donor owns or controls.

By contrast, elections for New York City offices, including for mayor and City Council, are subject to much stricter limits. Contributions to mayoral candidates are limited to $4,950 for an election cycle, which includes the primary and general elections. Corporate contributions are prohibited. Crucially, the first $175 of any individual’s contribution is matched six to one, meaning that a $175 contribution is actually worth $1,225 to the candidate. This magnifies the effect of small contributions enormously — and encourages candidates to seek them. The matching-funds program has worked well for nearly 20 years and has won high marks for helping to avoid the problem Mr. Vance is encountering.

New York City’s system is especially well suited for district attorney elections. Despite the great importance of the office, many politically active citizens do not appreciate its relevance to their daily lives and are simply not interested in contributing to those campaigns. Thus district attorney candidates often wind up relying on criminal defense lawyers, who are very much interested, for a good portion of their campaign funds. Sometimes district attorneys even resort to soliciting contributions from their own staff, despite the serious ethical issues of doing so.

It would be relatively simple to integrate district attorney candidates into the New York City campaign finance system. State legislation (and funding) would be required, but the administrative structure is already in place. The city law has different contribution limits for each office, including a $3,850 limit on contributions to borough president campaigns — district attorneys also represent boroughwide constituencies and could be treated just the same. Even if the application of city campaign finance rules to district attorneys is limited initially to the five boroughs, we expect that before too long citizens elsewhere in the state will demand the same practice.

Our experience leads us to strongly support the contribution limits and matching funds for district attorney campaigns. One of us was a City Council member who was elected under the city system and can attest to its value in eliminating candidates’ reliance on big-money donors. The other of us won her first election as Brooklyn district attorney after having been a congresswoman and a candidate for United States Senate, with widespread support. She was not reliant on the defense bar, and in her re-election had only token opposition. Even though her situation was unusual, she could see from her experience on the job that there would be pressure to take contributions from interested lawyers.

To be clear, we see no reason to conclude that campaign contributions are in fact influencing district attorneys decisions. But we do believe that public confidence has been significantly damaged by the recent coverage of Mr. Vance’s donors. Perpetuating the current system will lead to further erosion of public trust and risks actual corruption. It is time to end that risk.